European politicians wrestle with high gasoline prices

From the International Herald Tribune:

“It’s a very difficult situation for governments,” said Colette Lewiner, an energy expert at Capgemini, a consultancy. “What governments should be doing is lowering the tax on the oil products, but that would mean lowering their own expenses and breaking spending promises, so governments are trapped.”

A big worry is that fuel price rises are contributing to an inflationary price spiral. Another is that past increases have triggered paralyzing national strikes. But European governments rely heavily on fuel taxes to balance their budgets, drastically reducing the scope for cuts.

In France, for example, taxes on unleaded gasoline represent 62 percent of the cost of a liter of fuel at the pump, while taxes on diesel represent 53 percent, according to the Union Française des Industries Pétrolières. Those taxes are the largest source of state revenues after value-added tax, income tax and business tax, said the industry association.

There is a picture painted of a government needing excise revenues; I would suggest the flip-side: that bowing to the pressure from fuel-intensive industries would only promote an expansion in the demand-side pressures on oil – precisely the cause of our environmental (and many of our economic) problems.

For example:

French fishermen, who already benefit from hefty fuel subsidies, have mounted the strongest protests so far over fuel costs.

This month, the fishermen – some of whom use several hundred of liters of diesel each day to power their boats – blocked fuel depots in Atlantic coastal regions to draw attention to costs that have climbed to about 50 euro cents a liter up from about 30 euro cents a liter. Only below 30 euro cents a liter can fishing be profitable, they say.

Amid reports that some gas stations in Brittany were running dry, the fishermen went back to sea Thursday, after President Nicolas Sarkozy of France visited the Atlantic coast and personally offered concessions Tuesday.

What? The demand for fuel by fisherman is not the demand for fuel: it is the derived demand for fuel, and it is a function of our actual demand for fish. That is to say, we, the consumers of fish, demand fuel such as it is needed to get us that fish – in given quantities, according to price.

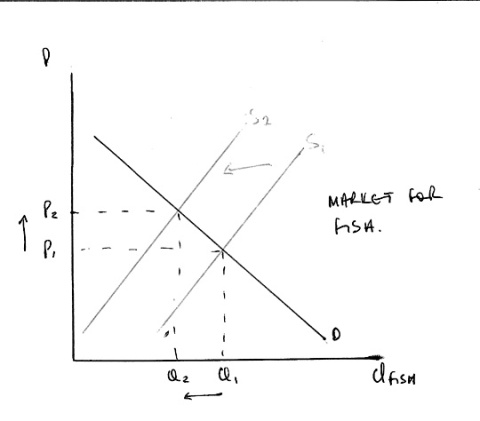

Implications? Oil doesn’t have to be manufactured – via subsidisation or differential tax exemption – to be 30 Euro cents per litre so that fishing can be profitable. Fishing has to decline in accordance with the decrease in the quantity of fish demanded. Some fishing operations (those with lower costs) will stay in business; others will not:

The effect of the firms that shut down because they cannot achieve profitability will reduce market supply, thereby increasing the price. This is the law of demand: as oil prices appreciate, fish prices appreciate; as fish prices appreciate, the quantity of fish demanded decreases.

Alternatively, everyone stays in business, and charges a price higher than P*, so that they keep making a profit. Rather than a leftward shift, the supply curve, above, shifts upwards – with the same effect. As oil prices appreciate, the costs of production (of fish) escalate. As the costs of production increase, the supply curve shifts backwards – but demand does not change. Therefore less fish is bought because people with the lower willingness-to-pay stop buying fish. For some firms, as in the first graph, this price increase will get back to where some intersection of MR and MC can be found – for some it may not. They either pack up and leave, or continue running (I didn’t bother with Average Variable Costs) and try to turn things around – by, say, picketing the government for lower excise duties on their fuel.

Basic economics. Cruel economics, perhaps, but basic economics. In this world, resources are scarce. This is the first principle of economics: resources are scarce, and allocating those resources is the defining problem of economics. Fisherman don’t get to remain fishermen because they’ve always been fishermen. They get to remain fishermen if we are prepared to pay the prices required for them to remain fishermen.

I realise we’re talking about already taxed fuel, here: at issue is not, simply, our willingness-to-pay for fish. That, too, however, was/is a consequence of a society-wide (political economy theory permitting) allocative decision-making process. If our opportunity cost of that tax revenue (or the environmental externalities of the fuel use) remains higher than the cost of losing jobs in the fishing industry, then jobs in the fishing industry have to go.

The article is quite good (to say the least). Further examples are (of course) agriculture and taxi-drivers. Agriculture becomes interesting because, like fish – but much moreso – national food security can become an issue (in which case we, as society/consumers, would be willing to pay what is required for that security. So far it would appear that, with regards to fish at least, either we aren’t, or we aren’t understanding the problem in those terms).

Leave a comment